Originally published at The Substream.

Spoilers.

Thrilling and dangerous, Ridley Scott’s Prometheus is the vigorous work of a mature director, returning with terrifying intelligence to the rigours and riddles of long-ago dreams. The film does as advertised. It is hard sci-fi, thickly woven with ideas. It scours the corners of the Alien taxonomy in order to construct a new, dense mythology, yet it gracefully taps the familiar constructs of its progenitor franchise again and again. It is, after all the hullabaloo, indeed a prequel; but in more important ways, it is an echo, a refraction, and an entirely new strand of DNA. Like the first minutes of familiarity that argue to our subconscious that we are within a recurring nightmare, Prometheus feels disturbingly familiar and compellingly new, all at the same time.

I am sure that as far as Ridley Scott is concerned, Prometheus is the first true follow-up to Alien. (Not unkindly, the film does allow a few gentle nods toward James Cameron’s sequel. The only Alien-related properties it uncategorically disavows are, of course, the Vs. Predator noise.) The direct coupling with the original Alien is underlined in the film’s opening title itself: watch how the roman numeral II holds the center of frame for a lengthy beat, before the other lines and dashes that make up the word Prometheus hastily join the image. In Alien, the first character onscreen during the title was a I. Scott does not suggest that Prometheus is the true Alien II lightly. Where the other sequels merely reframed the Alien’s lifecycle for their own generic purposes, Prometheus base-jumps off the intellectual architecture of Alien’s first twenty minutes, and glides towards a larger and more enervating set of ideas.

Prometheus is true science fiction, from tip to tail. If the Alien films used sci-fi conventions as a shroud for an entirely other genre, never pausing to contemplate the implications of their imagined alien life, Prometheus needs no such cloak. This is an Idea movie, and as such, it will infuriate as many people as it will engage – but that’s the price of poker, and the film is not coy about it. In Prometheus’ prologue, a humanlike creature of some kind stands atop a rocky precipice overlooking a waterfall, before dispersing some genetic material into the world via his own body. Is this the Earth? Is this the beginnings of us? If you are not ready for an Alien movie that deals in such vast, galaxy-spanning connections and conceits — The Da Vinci Code: A Space Odyssey — you’d better turn back now.

The germ of the story is this: the humanlike being from the prologue is from a race of Engineers who seeded planets across the galaxy with the basic genetic material for intelligent life. If gods created mankind and did so in their image, these Engineers are the gods we’re looking for — and so, the starship Prometheus is sent into the cosmos, to find the Engineers and learn their intentions.

From the outset, the music strikes a surprising tone. A lone French horn sounds a searching, hopeful phrase, an inversion of the falling melodies of Jerry Goldsmith’s music from the original film. The melody is a thesis statement on Prometheus’ ultimate intentions. The film is named well, and will dramatize the horrible personal and spiritual consequences for one naïve human’s (over)reach for godly knowledge. But the (excuse me) nearly Star Trekkian salutation in the score, which recurs again and again throughout, argues for something noble in us, even in our folly.

In its form, Prometheus rhymes gracefully with Alien. The story grid maps nearly point for point, and is further festooned with precise visual callbacks. There is a ship — here, it is often framed as such an infinitesimal speck against the vastness of the cosmos that its mission never seems like anything but hubris. The ship lands on a planet — a striking desert world made up not of stormy chaos but surprising, disturbing order, with pyramids and roads and (imaginary) warning signs saying Keep Out. There is a crew — not as convincing a crew as the Nostromo’s, with less human interest in the performances and (much) more pretense in the dialogue. There is a landing party — not space truckers but scientists, and surely the dumbest group of scientists ever put on film, forever rushing headlong into untested environments and poking at things that wriggle in the dark. There is a woman — Dr. Elizabeth Shaw. She is played by Noomi Rapace, the girl with the dragon tattoo, and nicknamed “Ellie” to verbally tap Contact – a film with which Prometheus will have significant thematic parallels. Ellie is a scientist, and a person of faith, which is an odd mixture. When asked how she can reconcile her Intelligent Design-ish stance on the Engineers against three centuries of Darwinism, Ellie merely says “It is what I choose to believe.” But she is no dogmatist; Ellie may believe in god, but she also believes that god can be found, and therefore described by science. She has questions for him. Richard Dawkins would like her.

And there is, of course, the Space Jockey. It will surprise no one who is even passingly familiar with Ridley Scott’s comments on Alien and its sequels to learn that the cornerstone of Prometheus is what the director considers to be the original film’s largest dangling thread — not Ripley, not even the Alien, but the dead oversized corpse in the derelict spacecraft, whose chest exploded from within. Now, I am not nearly as conceptually entranced with the Space Jockey as others have been, and further, I like my speculative fiction to leave some of its tendrils ragged, unexplained, to better populate the highways of my mind. It is somewhat desiccating on a basic intellectual level when the Space Jockey suit (yes, it is a suit) is cut open, and the bald, human-ish dome of an Engineer is found within. Ebert’s Law of Economy of Characters applies, so of course it was going to be an Engineer, but an enigmatic question has been answered, and answered definitively, and something beautiful in the history of film dies.

But this is part of the architecture. Memorably, at the tail end of Lost, screenwriter Damon Lindelof (who rewrote Jon Spaights’ first draft of Prometheus) made a very unpopular point about the ceaseless badgering for answers about the show’s mythology, by having a character utter the admonishment, “Every question I answer will simply lead to another question.” There is an interpretation — a valid one — that holds this line to be part of a kind of head-in-the-sand, shut-up-and-listen-to-daddy anti-intellectualism that ultimately ends all science vs. religion debates, on the religious side, with some variation of “Well, I just have faith.” And this notion is once again hinted at in Prometheus, when one of the characters asks, regarding the Engineers, “Yeah, but who created them?” But with these phrases, I think Lindelof is not telling us to stop asking questions, so much as he is alluding to the bottomlessness of all knowability — which is a humble idea, and key to Prometheus’ frame. It isn’t that we aren’t worthy of answers, or of the quest to find them; these things are human nature. But it is also human hubris to think we will ever arrive at some final, definitive solution to our searching.

Generously, Prometheus supplies us with a whole host of new questions, directions, and vivid new dreams. There is a Space Jockey spacecraft which crashes on the planet in Prometheus; but it cannot be the derelict visited by Dallas and Kane, so where’s that one? If we’re on LV-223, where is LV-426 (and why are we on LV-223)? What is the black goo? Who made the mural? Is the planet at the beginning of the film Earth, or LV-223, or somewhere else? And then there is the question of the Engineers themselves, who draw our crew and our heroine to this world and promptly try to murder her, and them, and all of us — why? The film’s greatest moment comes when Shaw realizes that regardless of whatever hostility the Engineers might have towards the human race, the loop is not a closed system, a single pathway between this planet vs. ours. These beings still came from somewhere else. When Ellie (with her faithful robot head sidekick!) decides to keep searching – the last lines of the film are a rhyme, but substantial alteration, of the last lines of Alien — Prometheus opens up a glowing universe of possibility.

Throughout, Scott is playing what I’d call the Kingdom of Heaven gambit: using a story set in an entirely other time and place as scenario for an energetic discussion of very right-now concerns. Prometheus is preoccupied with a very 2012 argument between creationism and evolution, faith and reason. The principal characters — David, Vickers, Janek, Charlie, Weyland, and of course Ellie — each have a unique stance on god that varies from holy faith to nonbelief, and a particular purpose in the story that ranges from a search for the actual Heavenly Father to a very meat-and-potatoes need to please, or kill, one’s biological daddy. Being devoutly of the “I’d murder god if given the chance” bent myself, I am well aware that it’s all part of the same story: the same questioning, the same sense of abandonment, the same desperate need to stand up on one’s own two feet and say “fuck you, I’m moving out on my own.” Even Ellie, the most religious character in the film, is packing her bags by the end.

The film’s most embarrassing blunder is the weird, needless casting of fortysomething Guy Pearce as hundredsomething Charles Weyland, thus subjecting a cringing audience to horrible old-age makeup for no apparent reason. (Pearce never appears as his true age — so why wouldn’t you just cast an old man? If this is sequel-baiting, for shame.) Second to this failing is the utter disposability of Charlie (Logan Marshall-Green), Ellie’s lover and partner; placing a romantic couple at the center of the drama is a fascinating idea, but Marshall-Green can’t pull it off. Charlize Theron, meanwhile, impresses as icy, needy Vickers, who achieves what Ripley could not, and murders a crew member to prevent the contamination of the ship. (Don’t you love it when the character to whom you are most opposed in a story is the only one behaving with a lick of rational sense?) Idris Elba gives an easy, entertaining performance as Janek, the captain of Prometheus, who here stands in for the more blue-collar crewmembers of the original Alien. He doesn’t give a fuck: he just wants to go home.

And then there’s Noomi Rapace’s off-kilter Ellie, who grins girlishly through the first half of the film and seems like a rather thin concoction, until she is standing bandaged and stapled inside the collapse of all her dreams, and becomes as ferocious and vivid a character as Ripley herself. I can’t stop thinking about her, and how impressively her character consolidates as the themes and plots of Prometheus unfold. But it is Michael Fassbender’s android David — his name suggests A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, another key thematic pairing — who will be the inevitable crowd-pleaser. David, who spends the years between the worlds boning up on Lawrence of Arabia (and does a sensational Peter O’Toole impression as a result), propels the story with singularly avaricious focus. It is David who wakes, and speaks to, an Engineer; it is David who dabs a thumbnail-sized blob of alien genetic material into Charlie’s celebratory champagne. “Big things have small beginnings,” he intones solemnly, and then things go completely haywire.

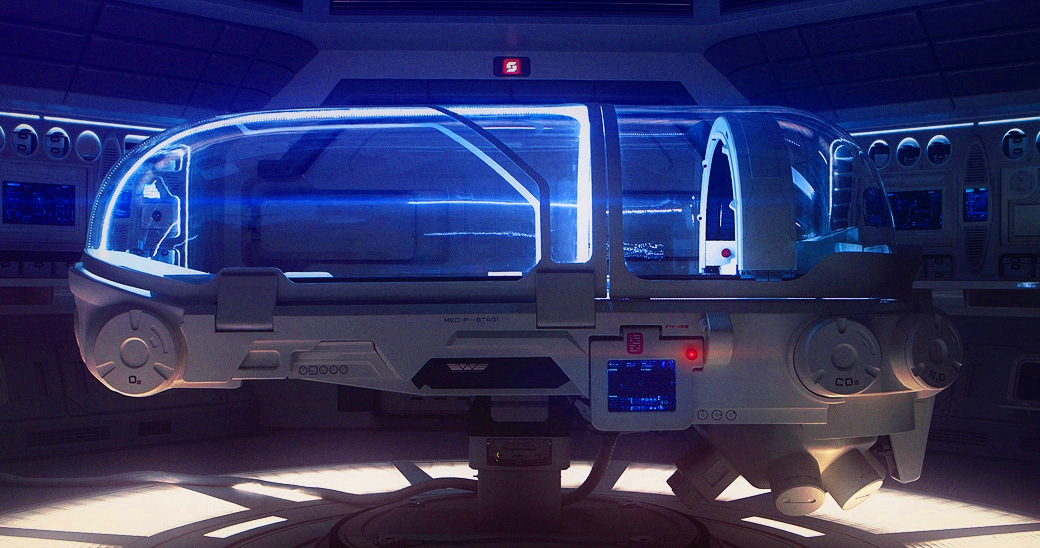

Oh right: Prometheus is scary as fuck. By the time it comes, I had rather forgotten that an Alien film could be, but when Ridley Scott takes the gloves off, panic-inducing pandemonium breaks forth. That dab of black goo from David’s finger infects Charlie, who has sex with Ellie, who finds herself pregnant with god-knows-what. The implications for the god-knows-what are big; by the end of the film we will have a pretty clear sense that the Aliens, as we knew them, were just one potential evolution of a weirdly aggressive froth of digital information that the Engineers were fucking around with on LV-223, eons before their demise. Ellie undergoes a self-surgery/abortion scene that has a good chance of inducing the fainting spells and vomiting attacks of the Kane sequence in the original film. This, the showpiece horror moment of Prometheus, is horrifying, repellant, and committed, boy, beyond any conversations about a PG-13 versus an R. The thing that comes out of Ellie – and the thing on the derelict that is awoken by David – and even the weird, apparently needless spider-thing that repurposes crewmember Fifield into a monstrosity — evince a very familiar primary genetic urge: adapt and survive. It’s a good thing for us, then, that Ellie ultimately manifests the urge as well.

There is something powerfully provocative about the symmetrical line of post-surgical staples which line Ellie’s abdomen after she gives “birth” to the god-knows-what. It is the first instance (chronologically) of a very H.R. Giger-ish biomechanical life in a film series that will make brilliant, iconic use of it. There is something equally provocative in the Not Alien that emerges, dripping, from the corpse of the Space Jockey in Prometheus’ last shot. No, it’s not the Alien. But given some generations of rapidly accelerated evolution, it will be. In a film whose principal character believes in faith-based creationism, Prometheus’ very notional nature argues for the opposite. The “strands of Alien’s DNA” that Ridley Scott promised would be found in the film are in how Prometheus suggests an inexorable genetic drive towards the icons and imagery of the original film, without ever itself being so cloying as to definitively arrive at them. Prometheus serves as a boilerplate upon which a surprisingly (and refreshingly) modern-day series of concerns are evaluated and stress-tested. And as Ellie, the rebel angel, takes off in an Engineer spaceship — the first character at the end of an Alien movie to be heading away from Earth, instead of towards it — Prometheus has the audacity to suggest an option beyond the old faith vs. reason dialectic. Prometheus argues that both answers are, themselves, incomplete, and that the search for knowledge, besides being our most essential human calling, is itself an act of faith.

Leave a Reply