“But the Joker cannot win,” a broken and defeated Batman pronounced at the end of The Dark Knight, conjuring a lie which drives the engine of The Dark Knight Rises. Terrorists always do win, is the problem; their part of the job is easy. All they have to do is shatter the certainty at the heart of a society, and into its vacant place will rush the tidal wave of turmoil that eats the thing from the inside out. Power is a trick — a shadow on the wall, to quote a recent television show — and The Dark Knight Rises clambers out of the rubble of the Joker’s chess game to observe the dissolution of power. In power’s place, we return to the basic thrust of Batman Begins: Gotham City needed a symbol, to pull itself out of chaos; and Batman gave them one.

Each Batman movie that Christopher Nolan has made has been suggested by its predecessor. If anarchic vomit reigned in Batman & Robin, the smartest decision Nolan or Warner Brothers ever made was to constrain the chaos by making a Batman movie about Batman-as-system. In Batman Begins, Bruce Wayne conjured the Batman as a response to a very specific set of problems, rather like a chemical reagent; he sent the reagent loose in the environment and let it do its work. This in turn suggested a sequel, where an equally canny gamesman entered the system and demonstrated that any game, once identified, can be easily overruled by simply playing against its base assumptions; that was The Dark Knight, which was — and remains — a spectrally canny piece of filmmaking. The whims of chaos and order batted the whiffle ball back and forth with such head-spinning zeal in The Dark Knight that to arrive at a faint-hearted moral equivalency in the final frames, where Batman takes the fall for Two-Face’s crimes, seemed like the kind of slender life preserver you cling to when the Titanic has gone down – no, it ain’t much of a salvation, but under the circumstances, we’ll take it.

The Dark Knight Rises opens eight years later, with that IMAX prologue sequence again; the one where Bane rips the tail off a plane in mid-air and Nolan stands defiant against the death of real-for-real, shot-on-celluloid Cinema by, y’know, ripping the tail off a plane in mid-air. If the sequence thrillingly introduced us to Bane before the tower-scaling antics of Mission Impossible 4 back in December, it’s a great shame that as a film, The Dark Knight Rises has very little more to say about the character; what you see is what you get. Bane is a giant thug with a whackshit voice and a thing over his face, and muscles so stupendous that they look like fat. He’s no Joker, and his “plan” — overthrowing Gotham and bringing Ra’s Al-Ghul’s destruction down on the city at last — feels so threequel (in the Scream 3 sense) that one spends most of the first hour of The Dark Knight Rises making “get on with it” hand gestures in one’s seat. We know where this is going, and Nolan being Nolan, I’m half surprised we didn’t start the film having already arrived there, before circling back to sketch the trivial, but elaborate, setup.

It’s amazing to me that even this filmmaker, on this project, has not escaped the drudgery of threequel dynamics; if The Dark Knight Rises gets away cleaner than, say, The Matrix Revolutions or Spider-Man 3, it’s nonetheless a far fucking cry from The Return of the King or Return of the Jedi. As is required of threequels, The Dark Knight Rises does indeed circle back on the storyline of the first film, bringing the League of Shadows — and Ra’s Al-Ghul himself, reincarnated in both young man and Liam Neeson form — back to the fore. The film faithfully introduces a raft of new characters whose presence in TDKR, by turns, often seem like needless distractions, given an already broad swath of established Gothamites from whom to draw, and to whom to give adequate resolutions. And the movie is self-importantly puffed up and long-winded, not unlike Bane himself, who waxes philosophical with the eloquence of a methamphetamine addict standing behind your house wearing an “I am the 99%” t-shirt. As a film, The Dark Knight Rises can match neither the inventive sense of fun of Begins, nor the clever thematic bombast (and propulsive, almost clinical, plotting) of The Dark Knight. By pedigree alone, Rises stands in the highest echelon of comic book movies ever made, and is a damnably good flick in its own right, which makes it all the more weird to pronounce it a marginal disappointment. The Dark Knight Rises is grandly ambitious, largely successful, thumpingly dramatic and pleasingly action-packed. It is not, however, as good as its predecessors.

At least, though, this is a film about Batman, which an unnervingly high percentage of Batman movies are not. The Dark Knight Rises focuses the lens back on Bruce Wayne, even if it does spend too much time toying with the already-answered question of whether he will resume wearing the costume. And once this is finally resolved — in a treat of a sequence where Batman resurfaces in high-speed-motorcycle-chase form — The Dark Knight Rises shutters Bruce again, sending him to the bottom of the Pit, a prison in middle-of-nowhere where toxic hope is maintained because it might, theoretically, be possible to climb one’s way out. It’s as emotionally nihilistic a note as I think I’ve ever seen played in a comic book movie, but as Gotham is crumbling on the news monitors and beyond, it provides a bottom from which to build to the climax — and build, and rise, The Dark Knight Rises does.

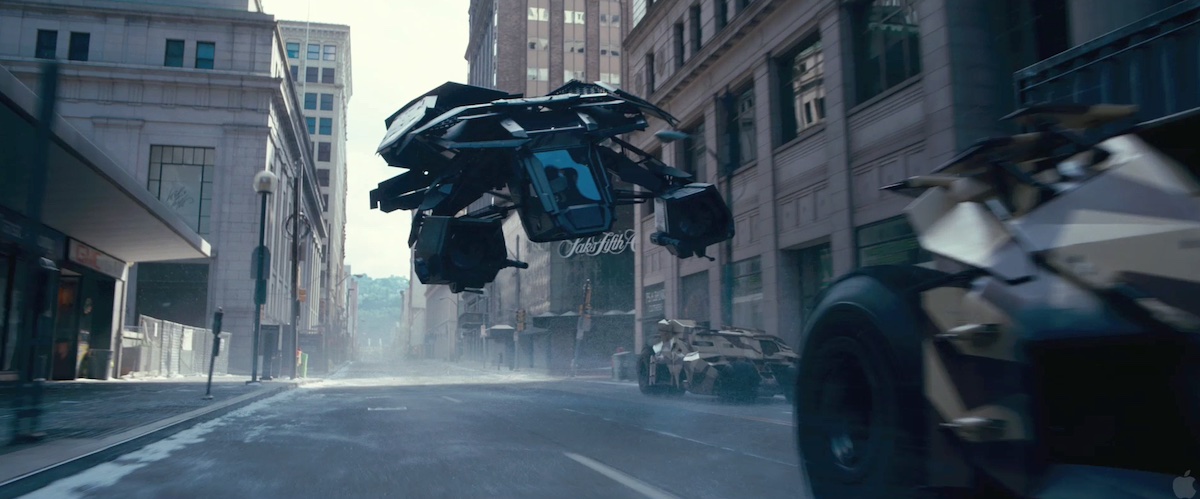

Current predicaments notwithstanding, we’ve had some good times with this Batman, and in the lead role, Christian Bale achieves a self-effacing easiness this time out that unifies both sides of the dual identity in a way I haven’t seen before. Given that the performance requires everything from regular dramatic scenes, to action beats, to messianic climbs to freedom, to that voice, to telling an actual joke in that voice (and quite a good one!), this is virtuosic. And if Batman will always be at least half measured by his toys, boy, the Bat-plane is a beauty. The Bat-pod gets a lot of good mileage in this movie, too, but any little boy who doesn’t get the Bat-plane under the tree this Christmas is going to stage a little Gotham uprising of his own.

The finality of Rises’ mission statement — Nolan et. al. quite definitely stepping away from the Bat-cave — allows for a throw-for-broke contour to the storytelling, as the filmmakers scramble to put their revisionist stamp on the last of the key archetypes of the Batman mythology, completing their trilogy as a kind of definitive take, a Magnum Opus of the Batverse. Sadly, still no Penguin, but The Dark Knight Rises provides — and indeed, rejoices in — dextrous interpretations of Catwoman and Robin; one very close to the cloth, one wildly and assuredly smart. In finding and fleshing out these last two missing pieces, each crucial counterpoints to Batman in their own unique way, the Christopher Nolan Bat-tapestry seems whole and complete in a way it couldn’t till now.

As a kind of loose reinterpretation of Robin, Joseph Gordon-Levitt as John Blake might not come as any great surprise — who else could Levitt possibly have been playing? — but I appreciate Rises’ willingness to draw a profile for the character that actually makes sense within this universe, rather than hewing to the existing mythology. The rewrite also lets Blake witness key events of the story and provide fiber connecting Batman to the far-ranging members of his entourage (particularly Selina, Lucius, and Gary Oldman’s MVP performance as Gordon), while still asserting a kind-hearted growth arc for Blake himself. He’s a dead useful character, cleverly performed and applied. The duel of the gods between Batman and Bane is nicely humanized by letting Blake come to understand each of them as flawed, frustrating men.

Catwoman, though, is my natural favourite. I spent most of The Dark Knight Rises under no real illusions about where any of the story was going — “Miranda Tate,” my ass — but if there was one element which consistently surprised me, it was the degree to which I was enjoying Anne Hathaway’s Catwoman. Nolan has a checkered history with his female characters, which makes this Catwoman a definite breakthrough: she neither exists to die (and thereby motivate) the hero, nor is she a vampish ball-buster. Though not as operatic or as complex as the Burton/Pfeiffer incarnation, Hathaway’s Selina Kyle fits into the Nolan rewrite of the mythos like a slender hand into a designer glove. Hathaway brings the physical chops, the hint of vocal purr, and a freshly dramatic moral arc to the role, and Hans Zimmer’s ascending dance of chords for her theme provides pulse-quickening excitement to the action scenes where she teams up with Batman. Selina is instantly credible, getting the better of both the good guy (Bruce Wayne introduces himself by shooting arrows at her head, but our cat burglar gets away with the jewels nonetheless) and the bad guy (Selina has a delicious set piece where she nine-lives her way out of a double-dealing client’s snare) within the first thirty minutes of the film. And true to form, Catwoman darts nimbly back and forth along the line of moral righteousness; neither good girl nor bad girl, she is completely, thoroughly agented. This makes her more than a match for both Bruce and Batman, and eventually, for the unified man who shows up in the third act to be both, and neither, and more.

The Gotham that Bane-as-warlord creates in the back half of the picture, where citizens are tried in the Scarecrow’s kangaroo court and the green-eyed girl who climbed out of the pits of hell hatches her final vengeance, feels like a kind of French Revolution fever dream. It strikes me as such a ballsy — and original — place for a Batman story to inhabit, that I could have watched several more three-hour movies just about life in the city under such extraordinary conditions. It’s a shame that The Dark Knight Rises only arrives at this point at the midway mark, and that the rest of the story isn’t nearly as convincing. Snow-strewn, patrolled by camouflage Tumblers and imprisoned under martial law, and of course shot for-real in the streets of Pittsburgh, Chicago, and Occupy Wall Street-era New York, the overthrown Gotham at the conclusion of Christopher Nolan’s Bat-universe is playing in thick, chewy images, but for the first time in the trilogy can’t cohere them down into a useful thematic point. It’s all action-movie bombast and satisfyingly generous emotional resolution, but it plays none of the speculative games of Nolan at his best, nor does it shine any kind of a light on the modern reality of social revolution from whose images of impending onslaught The Dark Knight Rises liberally pillages. No matter. The all-out war for the spirit of Gotham that unfolds in the skies and the sewers and on the bridges and beyond, as The Dark Knight Rises draws to a close, brings the world’s finest fascist to a rousing, Big Hollywood conclusion. Batman, built, shattered, and rebuilt over the course of three films, rises high. And Gotham City endures.