Batman arrived at the exact right moment in my young life to become the Thing With Which I Was The Most Obsessed for the entirety of the subsequent six or seven years. It eventually took, I think, about a year of Batman Forever hangover to finally cure me of the disease. When the first Batman came out, though, I was twelve, two months shy of thirteen. That was the summer of 1989, which was also, notably, the summer when everything else arrived: it was Hollywood’s first true “tentpole summer,” made up of not just the gargantuan peta-hit of Batman, but also sequels and franchise pictures varying from the second Ghostbusters movie to Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. It was a big year. I was at the movies all the time. And although I grew up an Indy fan, I went home with Batman that year.

Those of us who grew up in the 80s will remember that right up until Batman was on the screens, there was ample concern in the fanbase and beyond that Warner Brothers had gone completely the wrong way with the franchise. They’d handed it to a director whose two prior credits, Beetlejuice and Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure for cryin’ out loud, were as far from Gotham City as Cleveland is from the Los Angeles of Blade Runner. Burton had immediately cast his Beetlejuice star, funnyman Michael Keaton, who does not have a square jaw, as DC Comics’ renowned square-jawed hero. Lando Calrissian was playing Harvey Dent, fer chrissakes! And to the majority of the moviegoing public, who had never seen hide nor hair of The Dark Knight Returns, Batman as a property was still that show that played in reruns on weekday afternoons, where Adam West and Burt Ward beat up Vincent Price’s Egghead while wearing shiny velour capes.

Yeah. As a movie franchise, Batman was, for the last time in history, a dodgy proposition.

Any doubt that the Batman filmmakers had succeeded in their efforts, however, is quelled within seconds of the film’s start. As Danny Elfman’s eerie underscore seems to sound the approach of something sinister from the reaches of a distant mountaintop, we sink from a midnight blue sky down into – what? Weird, endless reaches of concrete with obscure curves, a post-Star Wars revision of the trench run that eventually pulls out to reveal itself as that single iconic image that ruled marketing for the entirety of 1989: the batsignal. Gods, that thing was everywhere that year; glowing from every t-shirt, plastered on every billboard, and (by Christmas) adorning every boy’s wall. The toothy, lantern-like elemental graphic, black on yellow on black. You could run Batman up a flagpole, and everyone in the world would know what you meant.

From the opening credits we are thrust into a definitive refusal of Batman’s kitsch value and a lasting assertion of a new, darker universe. An innocent family is robbed at gunpoint, and the criminals are subsequently dealt with by the revelation – first in rumours, then in form, and finally, in full-cape-spread ass-kicking – of the Batman.

To answer the most obvious of the concerns prior to the release of Batman, both Burton, and Keaton, are more than ample to the task at hand. Tim Burton, in retrospect, seems marginally overwhelmed by the scale of the movie, especially compared against his prior experience, but Batman is such a headlong rush regardless that any uneasiness the director might have felt around worldbuilding on this scale only appears in momentary glimpses throughout. Batman isn’t a very Tim Burton-y movie, true (except in some choice bits of casting – Jack Palance and Robert Wuhl among them), but in service of a project of this magnitude, the relative understatement of the director’s hand is probably a good thing. Batman established Burton as a business-driving visionary, rather than the obscure artistic nutjob that he might otherwise have become. And in bringing Keaton into the fold, Burton did what, in ’88 and prior, might have seemed impossible: he conjured a Batman who erased the legacy of Adam West.

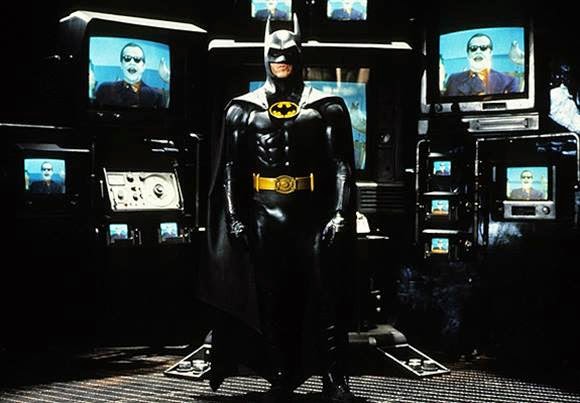

Keaton – funny, neurotic, and painfully shy – is hardly the Bruce Wayne of the comic book (his “playboy” exploits, including bedding Vicki Vale, strain credulity), but he is nonetheless able to revolutionize the public conception of the character by leaning into, instead of away from, the fractured duality at the core of the Bruce/Batman mythology. It’s a fascinating portrait, and remains definitive. Dressed in head-to-toe black rubber (which looks sort of stupid on DVD – the smoke and mirrors don’t hold up as well as they might have done to conceal the barely-working execution of the costume), Keaton even succeeds as an action hero. A far cry from the stalwart Supermanness of Christopher Reeve, we can thank Keaton’s Batman for the more inspired casting choices in the superhero genre ever since – from Robert Downey Jr.’s Iron Man to Heath Ledger’s Joker. Keaton was proof that you cast the actor, not the character, if you want to come away with memorable richness.

And he does, indeed, have the best toys. Batman (to its partial detriment) was less a story than an aesthetic, writ large for all to enjoy in the summer of ’89; the rubber batsuit gives way to the actual best Batmobile ever, even if the damned thing clearly can’t get above 30 miles per hour without cracking that fiberglass chassis. The Batmobile roars down leaf-strewn October highways in an operatic sound-and-fury sequence which is little better (and rightly so) than car porn; and by the time the Batwing is in flight, Batman has achieved the kind of holy-shit wow factor that might previously only have been the territory of Star Wars and The Wizard of Oz. And nicely offsetting the black-on-black-on-black fetishism of Batman and all his gear is the film’s single, poisonous colour-pop: the green-on-white-on-blood leer of the Joker.

It’s important to remember that Keaton was still only a mid-level star in ’89, and therefore found himself playing Batman in a movie called Batman where he nonetheless received second billing, behind the thousand-megawatt stardom of Jack Nicholson. Appropriately, Nicholson is a force of nature in the film, pimp-strutting his way around the juicy Joker dialogue with fearless panache and a genuine fondness for the character. He scared the bejeezus out of me in ’89 – adventure movie bad guys, in my experience, were not prone to spraying hydrochloric acid in supermodels’ faces, to say nothing of receiving rusty-scalpel surgery jobs in the middle of the night.

I don’t really buy the Nicholson Joker on a psychological level – dreary mob enforcer falls into a vat of goo and turns into a psychotic clown? – but he never fails to drive the engine of the plot and be consistently entertaining while doing so, which is a lesson nearly every superhero movie since could do well to learn and re-learn. (Cough – Amazing Spider-Man.) If Batman shambles along just as often as it truly engages – I’d say the film has a great first and third act, and a pretty flat second; and as a female lead, Kim Basinger’s Vicki Vale is sort of insanity-inducingly bad – then when the chips are down and there’s a big set piece to deliver, Burton, Nicholson and Keaton never disappoint.

Actually, the only real directorial miscalculation in the whole picture is Burton’s choice of visual effects, which augur back to Beetlejuice rather than forward to Terminator 2, and are needlessly cartoony, particularly during the Batwing sequence. That sequence is otherwise an all-thrusters masterpiece, even including such nonsensical grace notes as Batman piloting the Batwing into the visual center of the moon – which, of course, implies the existence of a single-camera vantage point that does not, and could not, exist. But whatever. Sloppy and risky and within a hand’s breadth of overreaching its ability, Batman was, and remains, a load of fiendish fun, and changed the game for comic book movies forever.