The sea calls us home.

After 2 and a half years of ducking it, I finally got it. The cove. It wasn’t too bad. (It was awful.) Knocked seven bells out of me, and (I realized this week), just disrupted everything, in a lot of small and not-so-small ways that I didn’t take the time to fully appreciate, once I was “back on my feet.”

By which I mean to say, I wasn’t really back on my feet. Not until the last few days. Now, my legs feel steady under me. Now, there’s some wind in the sails and calm water ahead.

I know water. Always have. How it flows, how it moves. As a child I was the self-appointed governor of a dozen miniature waterways; there was no garden I could not despoil with a hosepipe, turning a furrow into the Ganges, any given pond of standing water into a sheltered marina. My pandemic “panic purchase” two years ago wasn’t bottled water; it was a pond, with a waterfall, that flows all year, even in winter. (Especially in winter, when everything else — the entire world — has turned to ice.)

I was born in freshwater but come from salt — water so briny you can lay on your back in it; so rich it stands hair up for days, bleaching it dusky. I drove boats before I was ten; swam before I can remember. Touched the Mediterranean, stared out both “-most” points on the Atlantic (east and west), communed with the All in Hahei, New Zealand, feet in the surf, and thought about death and becoming. “You look completely at home,” someone said to me last month as I dogpaddled lazily around a charter boat in an inlet near the pirate cove near Rovinj, in Croatia. I swam under the ship and came back up on the other side, like crossing the road.

I had forgotten, some of it anyway. Three years without getting on a plane; five years without a cottage. No water. Height and air instead, and good walking on the earth; all fine things. But they are none of them the sea.

I left the sea behind in Sardinia, four years ago; saw it briefly again, off the shores of Yakushima, three years ago. Ate an entire flying fish, wings and all after being shown how, as I recall. In Rovinj I ate Istrian gnocchi on a patio outdoors, with three huge shrimp sitting indolently amidst the cream. (I didn’t know how, but I managed.) The shrimp — fat daddies — lent the whole dish the faintest, most pleasurable undertone of the sea. Something that had been missing, that I had not noticed gone, till I was tasting it there. Something, I realized, that might be a key to my blood; something from a hundred generations of DNA.

I was only in Rovinj for a little more than two days. It felt like twenty. It felt like it snapped the back of two long years. It didn’t, of course (and I lost my covid virginity immediately afterward, to prove it). Furthermore, now that I’m home, nothing back here has particularly changed. The world is simultaneously as angry as I’ve ever seen it, and completely and utterly dull; Toronto is more than a bit shit. I am trying to (and have no choice but to) ease back into post-travel life; but I’m tired of wealthy people, white people, and narcissists, and given that I am all three, I suppose I am tired of me.

Something that was waiting for me upon my return was the Refuge Vow, which I took with several other members of my Sangha, over Zoom, the day after I got back. When the opportunity to take the vow came my way my instructor asked me why I felt this was something I wanted to do now, and I said I didn’t know; I could only tell her that seeing the choice before me, it just felt “right” in some way that I could not define. My instructor told me that that was wonderful news, and a positive sign. I liked that, of course — the ephemeral sense that when something is right, it simply is; like falling in love, or knowing you’re the One in The Matrix, “balls to bones” — but I also spent more than a small amount of time in the subsequent weeks wondering why that sense of rightness came to me, or what it might mean.

I was reading Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche’s In Love With The World at the time, and thinking about the bardos; particularly the bardo of transition or becoming, the one that follows death. It should be noted that, nascent Buddhist or not, I don’t much hold with ideas of any material existence after the moment of departure, though like many atheists I suppose I would be happy — or let us say, amused — to be proven wrong. But of course, even in the context of the book, the bardo of becoming is not necessarily only the literal passage into the pure state beyond material reality. We die all the time; we die every day. We become all the time, from one thing into the next.

Or as I put it about a year ago, in my journal, in the white-hot cruelty of the summer of 2021, when I felt as untethered as I ever have, “I’m not falling… I’m landing.” Still am, I think. Nearly there, though.

My friends throw a hell of a party. A three-day party, in this case, which nicely fit my nearly-3-days experience. Like a great piece of music, it was all build, until the break — and the break felt huge, worlds-wide, horizon-to-horizon across an ocean of delirious love.

The wedding itself, though the centrepiece, was not the break. I hung out of windows and made chitchats and eye contacts. But no, the break came afterwards, at about exactly sunset, the day after the wedding, when many/most of us were cruising back across a cobalt sea from an evening cruise around the inlets, salt-kissed, beer-tipsy, and pretty much in love with the world.

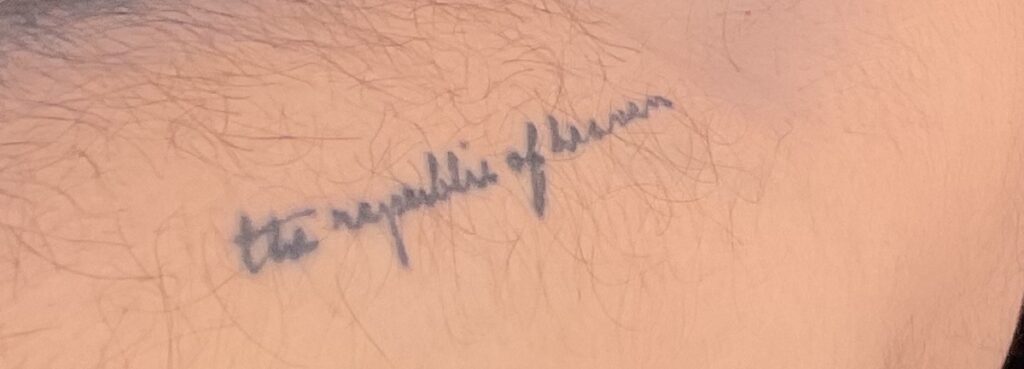

It has been a long pandemic — a long time in the bardo. The time in Croatia was not the end of the pandemic, as much as all of Europe seemed pretty fully convinced that the whole thing was long past worrying about. (Well, maybe it is. Past worrying about. Do you still worry about rain?) That last week in June felt like a point of transition, though, from a time of waiting to a time of moving on. We’ve all been waiting a long time, for a sign, a milestone, a thing that means we can wash all the valid and viable disappointment off ourselves and simply be where we are now, with a path ahead of us and some wind in our sails. I think when I was out there, back in the world, I finally found permission to be in motion again; and, I think I realized that home is no longer this dismal burg on the shores of Lake Ontario. The blood in my veins is full of salt.

“The world is not in your books and maps.”