Forgive me. With Indy 5 coming towards us, I had no choice but to look at my own writing archives, and resurrect this rave from 2003. Twenty years ago! Little has changed, save (I hope) my skill.

“The man is nefarious”

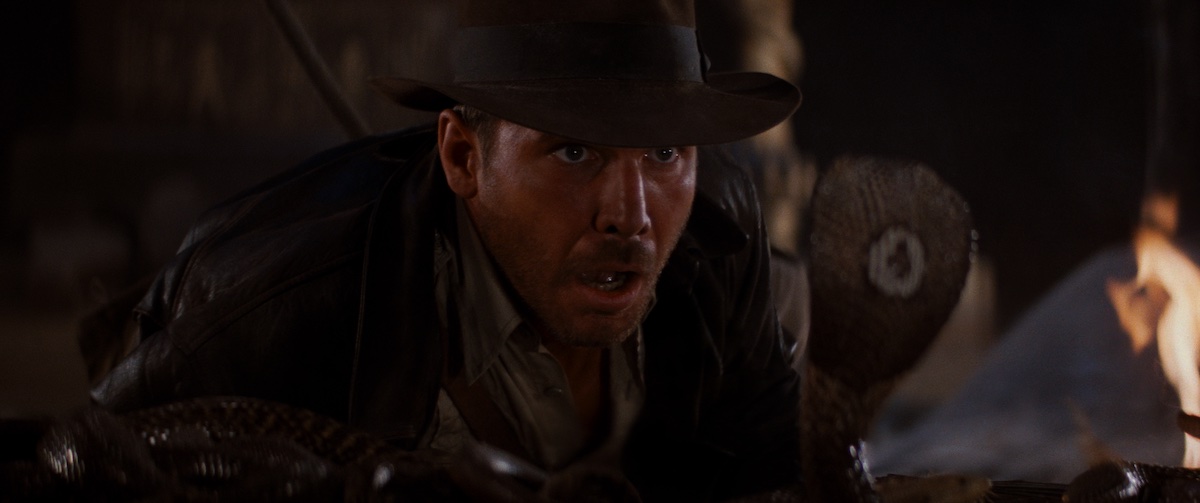

As this review is doomed to be an unparalleled rave from start to finish, let’s just get it out of the way early: films don’t get much better than Raiders of the Lost Ark.

There are a lot of films out there that are more artistic. Or more profound. Or even, in some cases, better made. But somewhere in the depths of Raiders is the heart and soul of film itself. If we can pin the invention of cinema on one man, and could go back in time to show that man Raiders, that man would have said: “Yes. This is what I wanted.”

It’s in the colours, in the sounds, in the heat and wind and light that seem to dance off the screen and into our minds when watching this movie. Raiders gets us inside. Raiders pulls us out of the movie theatres altogether, and takes us along for the ride.

Raiders of the Lost Ark is pure cinema in its greatest, unalloyed form. With the dialogue track removed, the experience of watching Raiders would change barely a whit; it’s the last picture show from a generation of American filmmakers who would soon single-handedly author the “tentpole blockbuster” mentality of the ’80s and ’90s, watching their audience forget the joys of smaller, slower things, that nonetheless do the job so much better than ten Minority Reports strung together.

Raiders is a tale told through a single language — imagery — that nonetheless leans on some great, crackling dialogue and workmanlike performances from an outstanding ensemble cast. It’s a tale told on a scant budget that hardly seems possible today. (The mind boggles when thinking of what Lucasfilm is about to spend to bring Indy IV to the screen.) It’s a tale told — god love it — on imperfections, great big quantifiable flaws that roll across the screen like tumbleweeds. And they make the picture better.

It begins — as all great things should — squarely in the middle. The middle of a trilogy yet untold, the middle of an adventure never seen. The middle of a simple problem: how does a rogue steal from the gods? Quickly, and deftly, and when all other devices fail, improvisationally. Raiders is a masterpiece of the most thrilling cinematic derring-do, the art of desperation. Perfect weight-replacement plan fails? Run like hell. Don’t got a whip? Jump the impossible chasm. Big rock? Don’t look back. And so on. And so on. Indy states it explicitly at the beginning of the truck chase, but let’s reiterate it here: “I don’t know, I’m making this up as I go!” Nothing ever works perfectly for Indy; he’s a master pragmatist who understands that, in the end, if it works, it doesn’t have to be pretty. And yes, it really is better to shoot the Arab swordsman than attempt to duel him. Honour be damned, Marion’s in trouble!

If the opening was designed to leave the audience completely satisfied after only ten minutes, it fails. There’s one worm wriggling through our mind, drawing that opening sequence, and us, directly into the film as a whole: who is this Belloq, and why do we hate him so much? Like that one kid in the classroom on the first day of school, you just know it as soon as you see him. Belloq – from the name down – is one of the slickest, slimiest, and endearingly human-est villains I’ve ever known. Paul Freeman headlines Raiders‘ supporting cast with enormous panache, but he is only the first of many. John Rhys-Davies, Denholm Elliott. Ronald Lacey. All among the most memorable performances of the past thirty years. Everybody knows the crazy nazi from Raiders.

And Karen Allen as Marion — unending delight. How well can you spit? How good can you look covered in dirt? How much charm, spunk, humour and sex appeal can you cram into one five-foot-five brunette? It is a shame, really, that Marion got rolled out so early in the Indy trilogy — she set a high water mark that could never be beaten.

How does a rogue steal from the gods? The South American adventure, not coincidentally, poses the same plot question as the whole darn film. As, notably, only Indy’s two advisors (Marcus and Sallah) seem to be aware, the film’s characters will spend its entire running time in direct defiance of the Almighty. It’s a dangerous game, full of storm-choked skies, portentous winds, and environments so hostile — from Cairo to the Well of the Souls — that they are often literally reaching out to ensnare our heroes. And of course, all of Indy’s heroism and bravery — we watch him be beaten to a pulp and back — leads him nowhere but to ultimate defeat. The fight with the crazed German mechanic, the truck chase, even the subterfuge on the pirate ship, are all wasted efforts, because at the end of the story, Indy and Marion are still tied to a pig pole, ready to be sacrificed to God. It is only the fact that in the face of this overwhelming understanding, Indy shows a little simple humility – mixed with an apparently excellent memory of Sunday school – that allows our heroes to survive the tempest in a test tube that Belloq is whipping up at the altar, while all around them are melting… melting….

So what we have here is a gobsmacking action film, one of the most entertaining summer spectacles ever made, that actually, in its final reel, dares to let the hero be inactive, a thinker rather than a fighter. Perhaps this is the exact moment that Indy became more than just a celluloid one night stand; maybe this is why the man in the hat has permeated popular culture for over twenty years. He’s more than just a guy with a gun who fights till he can’t fight no more – he’s us, as we hope we can be… under a boyhood fantasy of extreme circumstances.

Purist’s Note: The October 2003 DVD edition of Raiders is a digitally altered cut of the film created by George Lucas’ increasingly revisionist take on his early work. A number of “mistakes” from the film have been erased, including on-set gaffes such as telephone poles and support struts, and the infamous reflection of the King Cobra in the pane of glass separating the animal from Harrison Ford.

My objection to this is that it goes against the nature of Raiders as a film. Raiders was shot on a relative shoestring budget and at an incredible pace, and the result emulates the cheap 1930s serials in ways more invasive than simply the storyline. The removal of these “mistakes” does a great disservice to the overall flavour of the picture, and Mr. Lucas has made his own mistake by creating this altered version.